Yao's principle

In computational complexity theory, Yao's principle or Yao's minimax principle states that the expected cost of any randomized algorithm for solving a given problem, on the worst case input for that algorithm, can be no better than the expected cost, for a worst-case random probability distribution on the inputs, of the deterministic algorithm that performs best against that distribution. Thus, to establish a lower bound on the performance of randomized algorithms, it suffices to find an appropriate distribution of difficult inputs, and to prove that no deterministic algorithm can perform well against that distribution. This principle is named after Andrew Yao, who first proposed it.

Yao's principle may be interpreted in game theoretic terms, via a two-player zero sum game in which one player, Alice, selects a deterministic algorithm, the other player, Bob, selects an input, and the payoff is the cost of the selected algorithm on the selected input. Any randomized algorithm R may be interpreted as a randomized choice among deterministic algorithms, and thus as a strategy for Alice. By von Neumann's minimax theorem, Bob has a randomized strategy that performs at least as well against R as it does against the best pure strategy Alice might choose; that is, Bob's strategy defines a distribution on the inputs such that the expected cost of R on that distribution (and therefore also the worst case expected cost of R) is no better than the expected cost of any single deterministic algorithm against the same distribution.

Contents |

Statement

Let us state the principle for Las Vegas randomized algorithms, i.e., distributions over deterministic algorithms that are correct on every input but have varying costs. It is straightforward to adapt the principle to Monte Carlo algorithms, i.e., distributions over deterministic algorithms that have bounded costs but can be incorrect on some inputs.

Consider a problem over the inputs  , and let

, and let  be the set of all possible deterministic algorithms that correctly solve the problem. For any algorithm

be the set of all possible deterministic algorithms that correctly solve the problem. For any algorithm  and input

and input  , let

, let  be the cost of algorithm

be the cost of algorithm  run on input

run on input  .

.

Let  be a probability distributions over the algorithms

be a probability distributions over the algorithms  , and let

, and let  denote a random algorithm chosen according to

denote a random algorithm chosen according to  . Let

. Let  be a probability distribution over the inputs

be a probability distribution over the inputs  , and let

, and let  denote a random input chosen according to

denote a random input chosen according to  . Then,

. Then,

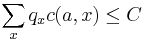

![\underset{x\in \mathcal{X}}{\max}\ \bold{E}[c(A,x)] \geq \underset{a \in \mathcal{A}}{\min}\ \bold{E}[c(a,X)]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/3c1efc8283d9c89b7529385560fc3a26.png) ,

,

i.e., the worst-case expected cost of the randomized algorithm is at least the cost of the best deterministic algorithm against input distribution  .

.

Proof

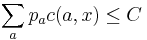

Let ![C = \underset{x\in \mathcal{X}}{\max}\ \bold{E}[c(A,x)]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/1bd70020e4698b8a15981db8dc9e7061.png) . For every input

. For every input  , we have

, we have  . Therefore,

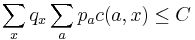

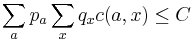

. Therefore,  . Using Fubini's theorem, since all terms are non-negative we can switch the order of summation, giving

. Using Fubini's theorem, since all terms are non-negative we can switch the order of summation, giving  . By the Pigeonhole principle, there must exist an algorithm

. By the Pigeonhole principle, there must exist an algorithm  so that

so that  , concluding the proof.

, concluding the proof.

As mentioned above, this theorem can also be seen as a very special case of the Minimax theorem.

References

- Yao, Andrew (1977), "Probabilistic computations: Toward a unified measure of complexity", Proceedings of the 18th IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS), pp. 222–227

External links

- Favorite theorems: Yao principle, Lance Fortnow, October 16, 2006.